…AND OTHER LESSONS LEARNED FROM CO-OP GAMES

Introduction by Peter Vaughan: Nicholas Yu is an active and positive collaborator on Facebook, Game Crafter, Kickstarter, Twitter (@yutingxiang) and at the League – so it’s ironic to me that he would have any issues with cooperative play!

Nevertheless, I was thrilled to get his thoughts on co-op lessons and tactical analysis of Sentinels, which gives insight not only into alpha gaming but also I feel reveals more clues about his own engaging deck-building design twist, Hero Brigade. So join Nicholas and find out which side of the co-op battle you’re on. Enjoy!

—

I recently picked up Sentinels of the Multiverse on iOS and my thoughts naturally turned to cooperative game design. I posted a few thoughts and questions to the Card & Board Game Designers Guild on Facebook, and that post created a lot of interesting discussion. The League was kind enough to give me space to continue to explore my thoughts and collate the responses I received.

It’s important to first understand that there are primarily two distinct types of cooperative games: Those that are fully cooperative and those that are competitive and/or utilize hidden information, often implemented as personal goals or traitor mechanics. In this post, I’m going to analyze the former, but here are some examples of both types of games so you have some more context.

FULLY COOPERATIVE GAME

Examples: Sentinels of the Multiverse, Pandemic, Pathfinder Adventure Card Game, Arkham Horror

COMPETITIVE COOPERATIVE GAME

Examples: Battlestar Galactica, Shadows over Camelot, Dead of Winter, Betrayal at House on the Hill

Fully cooperative games place everyone squarely on the same team. Players put their heads together and face off against the game itself and not each other. While individuals may ostensibly have their own characters, cards, and powers, all of the information between players can be freely shared and groups will often come to consensus decisions. There’s some very cool (and mind-boggling) game theory information that can be found on true cooperative board games.

These games work remarkably well if everyone functions as an equal member of the team and arrives at mutually agreed decisions by committee. They are, however, subject to armchair “quarterbacking” by an Alpha Gamer who thinks they know best who will try and dominate and specifically instruct the other players on how to take their turns.

Full disclosure: My original Facebook post posited that Sentinels of the Multiverse is perhaps best enjoyed as a single player experience because I didn’t have to deal with other people making sub-optimal decision.

There are times when a real human being, capable of empathy and other terrific human-type emotions, isn’t going to make the most optimal decision. That person drives me to Bananatown, USA and strands me there without my cell phone.

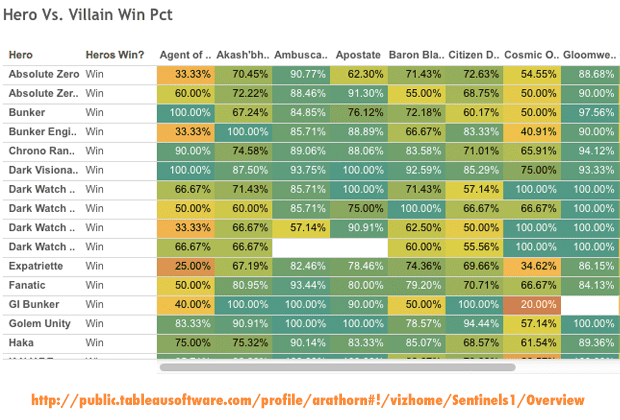

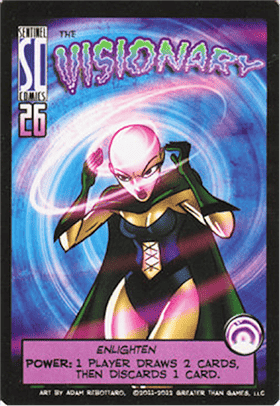

Consider an example from Sentinels. The Visionary is a powerful support character whose key ability is allowing one other player to draw cards. When I’m performing my elite Tempest “deeps” with Vicious Cyclone, I need to be fed cards. If you’re Visionary, keep giving me cards. Being fair and taking turns passing cards to the rest of the players is inefficient. If you’re giving cards to Bunker or Absolute Zero, you’re just throwing good cards after a lost cause. Vicious Cyclone with Gene-Bound Shackles (another key Tempest card) is going to be both more effective and more card-efficient than whatever Absolute Zero is going to do, and the discrepancy only gets greater the more damage buffs you throw in (such as from Legacy, another hero, or from the game’s Environment).

Not everyone will care about the specific effectiveness of each hero in Sentinels, but other people will care very, very, very much. That’s not just word count inflation, either, 3 “very”s was the bare minimum amount of “very”s necessary to convey how much those people care.

A person who cares this much about Sentinels will probably attempt to hijack or quarterback the game if the group is comprised of people who don’t care nearly as much. Group composition is always important when gaming, but I’d argue that it’s doubly so for fully cooperative games. It’s much easier for one person to ruin the experience for the rest of the table than it is in other types of games.

On the flip side, your gaming group may have someone who is new to the game or even gaming overall, and they’ll be more than willing to listen to the advice of veterans, playing the cards they’re instructed to play in the order they’re advised to. Bryan Koch (@BryanKoch) and Damien Lavizzo (@eldamien) brought up Pandemic and Forbidden Desert as other examples of fully cooperative games where someone can just coast and not take an active part, and that brings up questions about player agency.

Does one player really make an impact on the game? Is it all about the committee’s consensus? If you’re really trying to do your best to win the game, aren’t you better off letting your elite quarterback take charge, for the most part? Are fully cooperative games broken on a fundamental game design level, assuming that not every player in the group has an equal level of competency and everything in the game is perfectly balanced?

FULLY CO-OP GAMES ARE NOT BROKEN FOR THE RIGHT AUDIENCE

I started discussing ways you can counteract these issues, and that leads us directly into cooperative games with hidden information. By providing each player with specific individual goals that will often work at cross-purposes with other players’ goals, you’re throwing a scraplet into the ‘Matrix of Hippie Free Love Cooperative Gaming’. The political nature of a cooperative game becomes a totally different animal when players are forced to cooperate out of basic self-interest with the foreknowledge that they need to sharpen their knives and wait for another player’s back to present itself. Because they don’t fall prey to the issues of fully cooperative games, are co-op games with hidden information inherently better designed and more interesting?

The League’s own Mark Major (@shmitz) then pointed out various ways in which I was being a silly min-maxing power gamer. Guilty as charged. Quick aside: I totally made a 4th Edition DnD Rogue who could single-handedly drop a Solo monster (meant to be a challenge for an entire party) in one round. It was a fun novelty for me, but it made the game a nightmare to balance for the DM and the other players felt mostly irrelevant during combat (90% of 4th). Totes OP. When you play Sentinels of the Multiverse and try to take over the game, you are channeling my 4th Edition Rogue. That type of behavior goes against the spirit of a fully co-op game. I had an “Ah-ha!” epiphany when Mark talked about the communal journey being the point of such games. A few other voices chimed in about enjoying the support characters in Sentinels because they loved helping others and creating a fun experience for other players.

FUNABLERS

People like Mark who play truly cooperative games are fun-enablers, funablers, if you will. It’s just as important that the people around them are having a good time relative to their own enjoyment of the game. I learned that day that I am not a funabler, perhaps I am even an anti-funabler.

I love Battlestar Galactica. Dead of Winter is on my list of must-plays. Fully cooperative games cater to a very different audience for a very different experience than most other games. It’s a crime to dismiss them. A fun-crime. (Not that the crime itself is fun, it’s a crime against fun. I’m going to shut up about fun now.)

The major take-away from this article should be this: If you’re designing a cooperative game, don’t feel as if you have to add hidden information to it. It’s okay to make a game for the funabling audience. Be aware of the quarterbacking phenomenon, but don’t feel obligated to introduce specific rules or mechanics to prevent players from quarterbacking. Those people aren’t playing the game correctly, anyway.