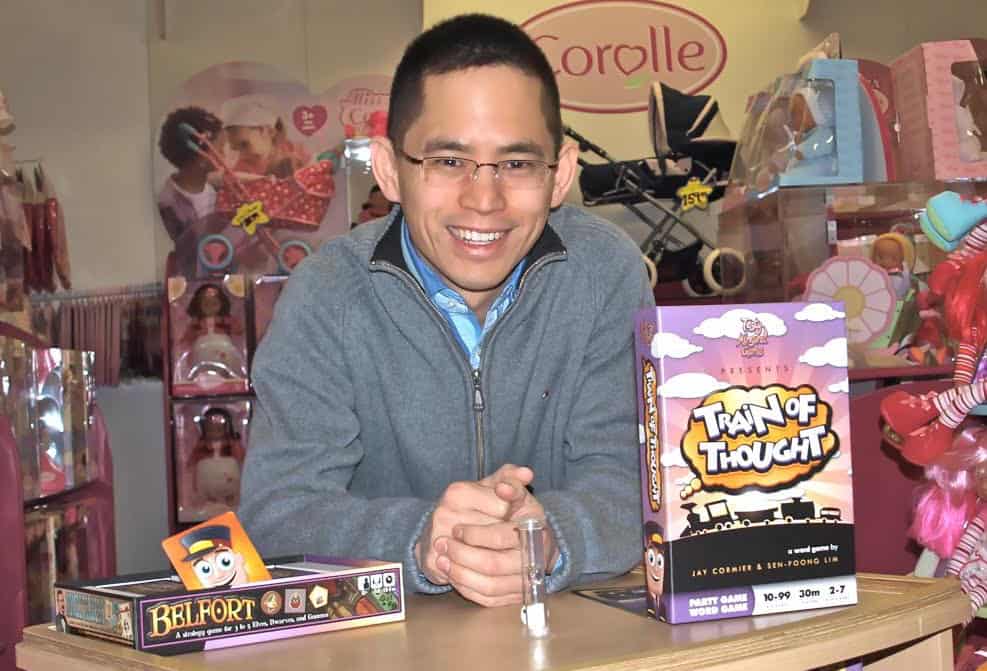

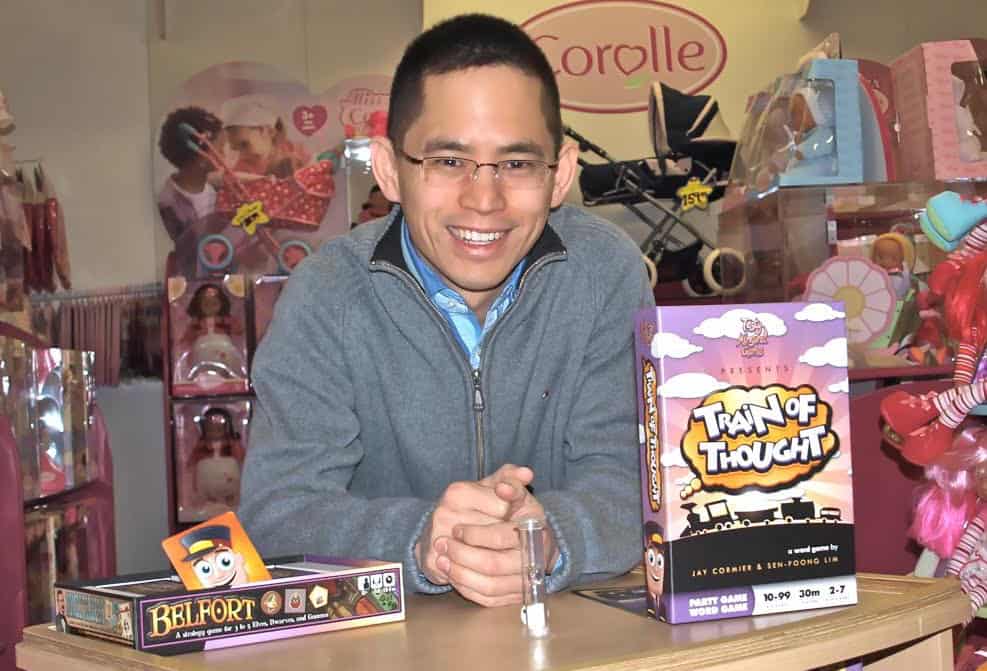

Sen Foong Lim has been seriously designing board games since 2005 with over ten published games, two shelves of prototypes and 15 active projects to prove it. Sen typically designs all of his games with a partner, usually Jay Cormier. By day, Sen is a college professor, teaching psychology at Fanshawe College in London, Ontario. By night, he co-hosts the Meeple Syrup show, a video podcast featuring board game industry guests. Sen considers Akrotori to be his best game, though Belfort has likely sold the most copies having gone through several print runs, and Junk Art, his recent dexterity game from Pretzel Games, is quickly catching up. Belfort also has the distinction of winning the Geekie award, Best Tabletop Game in 2014, and Dice Hate Me Game of the Year in 2011. I interviewed Sen via email to learn more about the Game Artisans of Canada and to get tips on how to design games with a partner.

What is the Game Artisans of Canada?

SEN: It’s a group of like-minded individuals; Canadian analogue game designers who strive to help each other make strides in the industry through mutual assistance and support.

What is your involvement with this guild? Why did you decide to get involved?

SEN: I’m the Steward of the London Chapter, which sounds really fancy, but it’s not really! I wanted to get involved because I like people, though mostly from a distance. Being introverted, on-line relationships are easier for me to manage and more effective for me as well.

How big was the guild when you joined? Now, how big is it? How big can it get?

SEN: When I started, it wasn’t much more than 20 people I think. Now it’s up over 50 with a huge list of accomplishments among us all. I think it can get bigger as we don’t yet have official chapters in some of the provinces or major cities across Canada.

How has the guild help grow you as a game designer?

SEN: It’s shown me the mutual benefits of mentorship, it’s introduced me to people that I am honoured to co-design with, and it’s opened doors for me that otherwise would be closed.

Which of your games have gone through the guild? How did the guild help make them better?

SEN: A large majority of our more recent games have been tested through the Game Artisans. They become better mostly in terms of rules clarity. We know how to build fun games, but the Game Artisans helps ensure that the intent is translated through the rules and the presentation of the game components. The chapters give us a lot of feedback in playability and small tweaks that help make the game even better with each iteration.

How many games have been tested by the guild? How many meetings has the guild hosted?

SEN: The GAC is run on a chapter basis; so there’s a Vancouver chapter, an Edmonton chapter, a Toronto chapter, etc. I can only speak for our own chapter – London runs at least biweekly if not weekly playtest sessions with usually 3-5 designers present. Some of the other chapters meet less frequently but have more members and vice versa. I was compiling some of the GAC accomplishments a few weeks ago and we have just shy of 100 games self-published, published or signed between all members. It’s actually pretty amazing!

Is the guild membership pretty steady, or do people come and go?

SEN: It’s typical a “member-for-life” situation – there’s no real reason to leave unless you’re no longer designing games. We don’t have people leave often.

How exactly does the apprenticeship work in the guild? How do members learn how to be good mentors? How do you keep encouraging struggling apprentices?

SEN: The mentorship process has each Journeyman attached to an Artisan. The Artisan guides the Journeyman through the game design process, allowing them a lot of latitude and mainly giving advice towards helping the game get better and linking the Journeyman to resources they might not otherwise have had. Encouragement comes from transparent feedback that is open and honest to help people make good games even better than they were before.

SOMETIMES, THAT IS THE BIGGEST HURDLE JOURNEYMEN NEED TO OVERCOME – LEARNING HOW TO BOTH GIVE AND RECEIVE USEFUL, ACTIONABLE FEEDBACK.

How are apprentices matched with members? What happens if a particular partnership doesn’t work out?

SEN: Typically it’s geographic, but as we come to rely more and more on social media and other online tools, we’ve seen mentorship bridge geographical divides. The matching process is typically done such that the Artisan agrees to take on the role with a specific Journeyman – sometimes it may be the Artisan who nominated the Journeyman for membership in the first place!

How much of game design is an innate talent and how much is a learned skill?

SEN: The design of the game itself is probably as much talent as it is skill. What happens after that is more skill based than innate talent, I believe, like rules writing, graphic design, etc.

These days, many colleges have majors in game design. Is this a good thing? In the creative writing world, there is much debate about the value of getting a MFA in creative writing, that you can’t teach good writing, that teachers are just pushing their own prejudices on their students. Do you think this sort of debate makes sense in the game design world?

SEN: I actually see it as a good thing in many ways. Most of the game design diplomas / degrees are in video game markets. What we’re seeing is the use of analogue game design (card and board) to help students of the digital realm recognize what good game design is vs. high polygon count, texture maps, and destructible environments. So much of video game design is hidden “beneath the hood”. Analogue game design allows students to work on making a game without having to have the baseline skills in programming, modeling, etc. that they’d need to make a full video game. It allows them to iterate quickly and work on teams – a skill that will translate well to video game design.

Is there any common game design advice you feel is misleading or largely wrong?

SEN: You know, I’d say that all advice in the game design realm is right, depending on the game, the designer, and their audience. I know that’s a bit of a cop out, but the truth is that a lot of how applicable a piece of advice is depends greatly on those factors. What works for one game may not work for another, due to a thing as simple as personal preference. Sometimes, you DO need a good-looking prototype.

Do you feel like the body of work produced by the Game Artisans of Canada embodies certain game design philosophies? If so, which ones?

SEN:

I THINK THE GAC DESIGNS MIGHT BEST EXEMPLIFY A CORE DESIGN PHILOSOPHY OF “LESS IS SOMETIMES MORE”.

I find GAC designs, by nature, tend to be less over-produced.

Why should a game designer consider designing with a partner?

SEN: Because then you can share in the joy of bringing an idea to life! It’s a great relief to have someone “get you” all the time. It’s wonderful to have someone to bounce ideas off of who can comment in a meaningful way. It’s also really good to have someone to ego check you when you think you’ve come up with “the greatest idea EVAR!” (again).

Where is the dividing line between someone who has made very significant suggestions to your game and an actual game co-designer? Have you ever tried to recruit someone to be a co-designer for your game based on their suggestions?

SEN: I’ve never had to recruit a co-designer – it’s always been that way from the start. I really enjoy working in pairs or trios or more! I find my choice in co-designers is always someone who complements an area of deficiency on my part. I’ve definitely come at it from the other end, asking if I could be a part of someone else’s design – this is always left to the original designer’s decision. I give advice freely with the understanding that sometimes, that may be all it amounts to.

What are some tips you would give someone who wants to try designing a game with a partner but who hasn’t done it yet?

SEN: Find people you can communicate with first and foremost. Strong interpersonal communication skills from both parties is very important in maintaining a healthy working relationship.

What are some of the mistakes you have made in co-designing and how do you avoid them now?

SEN: Probably not communicating how busy I was with other things has been the one mistake; sometimes one pulls more weight than the other and doesn’t see where they are not lifting as much weight in other areas.

How would you describe your roles in your teams?

SEN: I typically am the idea starter, the wordsmith, the connector, and the planner. I get sparks of ideas all of the time – it’s like breathing for me. I’m very word-capable, so I will edit and edit and edit things down to the crux of the rules. I see links between things and people all of the time, so I enjoy putting them together. For example, I typically pick who to pitch to and write the pitch up. I also understand how systems work and so can figure out which publishers need what kind of games and when. This is invaluable for setting up a strong pitch.

How do you decide which projects to work on or where to put your energy as a team?

SEN: Basically, it’s “follow your nose”. If one member is interested, it usually goes somewhere. If both members of the team are focused, it flies onto the table. If interest dies, it gets relegated to the lower depths of our forums until it might percolate up in later years.

In terms of dividing the work, is a 50/50 split realistic? Should a 30/70 split still be considered a successful partnership? How do you keep resentment at bay?

SEN: I think 50/50 is the optimal split, of course, but it should be understood that not everything is always 50/50 all of the time and that feelings are often far from the truth. A 30/70 split can be a successful partnership if both partners agree it is and if the outcomes are as equitable as the partners wish them to be. The other thing to note is that sometimes, one partner will do a larger percentage of a certain thing because they are faster / better / stronger at that part of the job (e.g. writing rules or laying out cards.)

REALLY, A LIFE RULE IS THIS: DON’T COMPLAIN ABOUT THE WORK SOMEONE ELSE DID ON YOUR BEHALF. THAT JUST CAUSES RESENTMENT.

How do you resolve creative conflict where both designers have strong opposing ideas about how the game should be designed?

SEN: We let the playtests speak for themselves. We are so beholden to the playtest now, because we’ve seen how it just brings the heart of the matter to light in terms of balance, structure, set up, etc.

Or, have you ever had a case where one designer feels a game is done while the other feels like more work needs to be done?

SEN: I think that has more to do with the stage of the game – is it ready to pitch? Does it need more content? Is there development to be done? You can only work so much on a game without direction from the potential audience (in this case, the publisher) and so sometimes, effort is better spent on working on something else, making a sell sheet, etc.

Do you ever make branching versions of a design, test them independently and then try to merge them back together later?

SEN: Yes, we’ve done that before where we have two or more ideas in play. We’ll try them all and then bring feedback to the shared table to dissect what worked and didn’t.

Have you ever met some of the famous German design teams such as Inka and Markus Brand, or Kramer and Kiesling? Did they give you any words of wisdom about the secret of their success?

SEN: Nope – Jay’s met Kramer in Essen, I think!

In terms of sitting down with a publisher, does it help to have an extra person at the table to help with the pitch?

SEN: Undoubtedly. Jay is typically the voice and face of the pitch, while I’m the hands. He’ll be talking and pitching, using the sell sheets to gauge publisher’s interest level then feeding back to me so I can set up specific games in specific scenarios, etc. I’ll then clean up while he pitches the next game. I’m typically the one who sets the convention schedule and meeting times/places, so I take care of the logistics, leaving Jay to worry specifically about being “on” for the pitch.

Do you feel like publishers treat design teams differently than solo designers?

SEN: I don’t know if they do, but there’s really a benefit to working with a team of designers in my opinion. We’re twice as good looking.

What is an upcoming project of yours that you would like to highlight?

SEN: Our next release is a D&D licensed game through WizKids called Rock Paper Wizard designed by myself, Jay Cormier and our fellow GAC member, Josh Cappel. Josh first worked with us on Belfort as the artist / graphic designer and we’ve been pals ever since. This is our first game together as a design trio, but definitely not our last! It’s a fun and fast game where you use hand signals to hurl spells at each other to comedic effect all while trying to steal the most gold from a dead dragon’s hoard. It’ll be out in Q1 2017 so look for it!

All pictures provided by Sen Foong Lim.