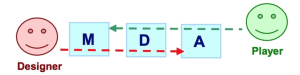

If you make board games, you should add [MDA] – Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics to your tool chest. Even if you just like to play and discuss games, understanding the framework can give you a new context for describing what part of your games you enjoy.

MECHANICS, DYNAMICS, AESTHETICS,

AND BOARD GAMES:

In addition to talking about [MDA], I also look at great dynamics from three games.

FRODO AND SAM: LORD OF THE RINGS: THE CONFRONTATION

MECHANICAL BEASTS: STEAMPUNK RALLY

TIMED DEMISE: DRAGON’S GOLD

THE ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER ON MDA:

MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research