Lately, I have been working on two heavier designs. One is an upcoming release to come out at GenCon and the other is a new co-design with fellow Leaguer, Luke Laurie, which we’re calling “Rising Tide“. I have spent a lot of time watching players making decisions on these meatier games and I want to share some of the insights I’ve had about decision making.

DON’TS

- NO CRITICAL DECISIONS ON THE FIRST TURN

First time players don’t know your game yet when they start playing, so they shouldn’t be asked to make a critical decision right from their start that may doom their game play.

I hate to pick on Catan, but based on my experience the first decisions in the game are some of the most important: where to place your initial settlements. Bad initial placements can definitely doom a player. There are a lot of things to think about: the frequency and distribution of the resource numbers, which resources the player has access to initially, the potential places the player could go next, and the position of 2:1 ports that might combo well with your settlements. How is a first time player supposed to grok all of that? They simply can’t.

In one of my designs, I considered giving players a starting hand of potential goals and letting them choose which ones to keep. I realized quickly this was a bad idea. How could a new player possibly judge the difficulty and value of the various goals, or how certain goals might combo well together? They can’t.

- KEEP DECISIONS OUT OF UPKEEP

Many heavier games have some sort of upkeep. Maybe resources come out every turn. Maybe cards come out every turn. It’s tempting to want to involve players in this upkeep. Maybe you should let players help decide which cards in the supply should get discarded. Maybe you should let players decide where various resources should be seeded. Don’t do it. While occasionally, these sort of upkeep decisions might be interesting for players, most of the time they suck up a lot of unnecessary time as players ponder the possible ramifications of putting a resource in this province vs. this province. For the other players, this delay is not fun.

REMEMBER, UPKEEP IS NOT FUN, SO TAKE DECISIONS OUT OF UPKEEP AND MAKE EVERYTHING HAPPEN IN A WELL-UNDERSTOOD, DETERMINISTIC FASHION.

In one of my designs, there were different sets of buildings available to be built. Occasionally, a special building would come out and replace one of the other buildings. Initially, I had players decide which normal building got discarded and replaced with the special building. I quickly saw that players took way too much time pondering this decision when it really didn’t matter and it only slowed down the game, taking time away from the really fun decisions in the game.

- BE WARY OF NON-TRIVIAL MID-TURN DECISIONS

Ideally, in meatier games, a player can think about their next move while other players are taking their turn. When it’s finally that player’s turn, the player can execute their well-crafted move and then the next player can take their turn.

However, I’ve noticed in some games, a player’s move might trigger a certain event or offer variable reward which the player can choose. In other words, the player might suddenly have to make a non-trivial decision they weren’t expecting in the middle of their turn. A classic example would be a player activating a power that lets them search through the discard pile for any card they want. As you might expect, these sorts of mid-turn decisions can slow down a game a lot. Other players are waiting while the current player has to reevaluate how to take best advantage of this new information.

In one of my designs, the player can gain a variable reward when they complete a certain goal. While the player might have planned out their turn in advance, they usually hadn’t considered what reward they should take, so when it came time to claim their reward, the player would usually stall and try to carefully consider their options. I still really liked this feature, but I tried to minimize how often this would happen so it wouldn’t continue to disrupt the game flow.

DO’S

- EVERYONE CAN UNDERSTAND WHY THE WINNER WON

How often has this happened to you while playing some Eurogame? The game ends, the score is close, but everyone looks around uncertain why exactly the winning player won. This is often the critique of so-called “point salad” games. If every decision gives you points, it can be hard to figure out which decision was the most important.

Sorry to pick on a published game, but I found my first plays of Hacienda on yucata.de to be puzzling. I was losing badly, but I really didn’t understand how the winners were winning. In the game, everyone is claiming land tiles, placing animals to reach markets and trying to be near water, but it was hard to parse which of the various ways to get points were most important. Contrast this with a similar game, Kingdom Builder , which has 3 main ways to get points every game. As the points are calculated at the end of the game, it is usually obvious how the winner won—they scored amazingly well in one or more of the 3 main ways to get points.

What advice can I give? I think it helps to have a hierarchy of points in the game. Players will naturally pay more attention to the 20 point actions than the 5 point actions. When the winner completes 4 20 point actions, that makes a bigger impression than if the winner made 10 different 8 point actions. Who can remember all those actions? In my current designs, there are definitely landmark ways to get points that stand out from the rest and are the source of the winner’s victory.

- LOSERS CAN UNDERSTAND HOW THEY COULD HAVE WON

The reverse of the previous point is that losing players should be able to think back over their play and say, “I see. I should have done that instead.” If instead losing players have no idea what they could have done to win, that’s a problem. This means either players do not understand the system of the game and how different elements work together, or players feel like too much of their fate is determined by luck.

In the first case, it’s helpful to structure turns and the layout of the board to reinforce the game system. You do this to get this which in turn gets you points.

IF THE GAME IS A FLOWCHART OF CAUSES AND EFFECTS, IT’S HELPFUL IF THE ARROWS ARE ALWAYS GOING IN THE SAME DIRECTIONS.

Allowing every element to affect every other element in unexpected ways may sound like an innovative idea, but it may also confuse players as to how the system is supposed to work.

If players feel like their fate depends too much on luck, then maybe certain cards are not balanced. You wouldn’t want a player to always win or lose if they draw a particular card. Or maybe the cards are balanced, but only if all players are experts. If there is a card that only an expert would know how to use well, then maybe that card would be better to include in an expansion then in the initial release of the game.

- PUT A CAP ON TURN LENGTH

In many games, there are often ways to gain extra actions which in turn can lead to more extra actions which might lead to even more extra actions.

WHILE CHAINING ACTIONS TOGETHER CAN BE FUN FOR THE PLAYER DOING THE CHAINING, THE REST OF THE TABLE IS WAITING FOR THE PLAYER TO FINISH THEIR 10 MINUTE TURN.

I think allowing for some extra actions might be OK, but I think having a limit is a good idea. Sometimes games have a certain number of actions, but then they also have optional actions which can also be performed which don’t count as normal actions. This may sound like it increases player freedom, but it likely can lead to unexpectedly long turns. Good players will naturally want to take advantage of every extra action they can do, so put some limits and make sure all (or nearly all) actions are included in the limits.

In the early phase of one of my designs, a player could take up to 6 actions on their turn. It could lead to some crazy good plays, but it was also leading to some crazy long turns. I realized quickly I needed to reduce that down to 4 actions. 4 actions still allowed for clever play without adding too much time burden on the game. In that same design, I added upgrades which gave players new special actions they could do. I made sure even these new special actions obeyed the same 4 action limit so that players’ turns weren’t getting longer even after getting the upgrades.

- HAVE A COMMON THREAT

I need to give Luke Laurie credit for this idea. In addition to having players compete against each other, the game can become even more compelling if the game also competes against all of the players. I am not talking about a cooperative game. I am talking about a game that throws threats at the players as they play.

In The Manhattan Project: Energy Empire, designed by Luke Laurie and Tom Jolly, players are competing for energy and buildings while constantly having to deal with pollution in their environments. In another game prototype by the same designers, players have to protect their workers against comets while also competing for precious resource spots and planets.

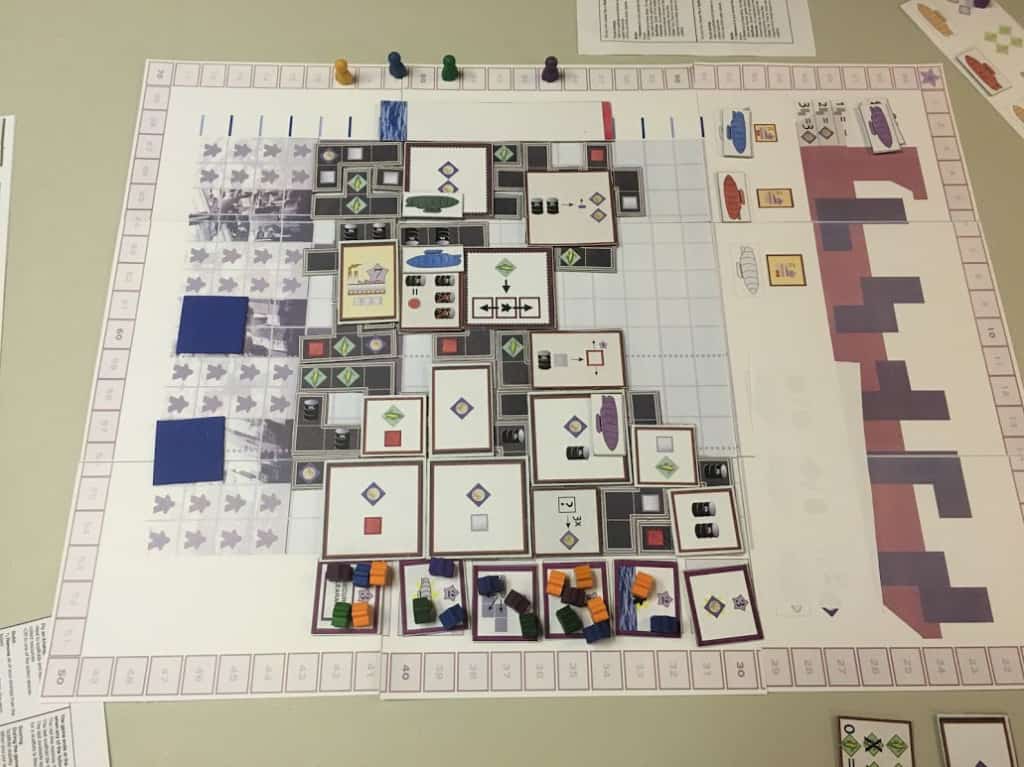

The decision space gets more interesting when a player has to weigh how to deal with so many threats and it can help to balance out different player skill levels. In Rising Tide, players are constructing buildings and moving engineers in a dystopian city while having to deal with rising waters that threatens to drown their engineers and flood the buildings. It’s delicious fun trying to deal with so many challenges.

- ADD SPATIAL DIMENSIONS TO DECISIONS

You can check out a whole post I did about Spatial Games, but I am definitely biased toward spatial decision making in games. I believe that spatial aspects literally add more dimension to decisions without necessarily making them more complicated to understand.

Auction games don’t usually have spatial dimensions, but then you play a game like Metropolys and you see that they can. In Metropolys, players bid where skyscrapers can be built, by placing numbered buildings on the board. Each successive bid needs to be a higher number and in an adjacent position on the board. Clever players can box in other players based on where they place their bids/buildings.

In Rising Tide, we took as a starting idea, “let’s make a spatial worker placement game” and I think we have succeeded pretty well on that premise so far. Stay tuned for more details as the game develops.

What do you think? Do you agree or disagree with my points? What advice would you give about decision making in heavier games?