You know this game, inside and out. It’s easy to learn, but as you’re talking you see the wrinkle forming in between their eyes. Another’s eyebrow just arched up. They’re not getting it. Why is this harder to explain than you thought?

A lot of people have trouble teaching a game to other people. Most of the time, it’s just in the delivery.

STEP 1: CONTROL THE TABLE

I’ve seen people sit across the table from me trying to tell me how to play a game while others are setting it up. The problem with this is that you’re not in control of the table. When you start talking about cards or some other component, you need to be able to grab those, show how they work, etc. If someone hasn’t gotten them out yet, it makes your presentation stumble and they start to lose interest.

You should be the one opening the box. As you take out the board and components, name them, give very little brief descriptions. It’s okay to say you’ll tell them more about something later. Right now you’re just introducing the components. If something catches their eye and they grab for it, take it back. Cool artwork or interesting components can be very distracting. Take it back and tell them you’ll get to that in just a minute.

If there are other players who know how to play, hand them cards or other components to shuffle and arrange as needed. If others try and chime in, stifle it. This is your table right now. Only one person should teach. Teaching by committee is the fastest way to make a person feel overwhelmed. This is your table.

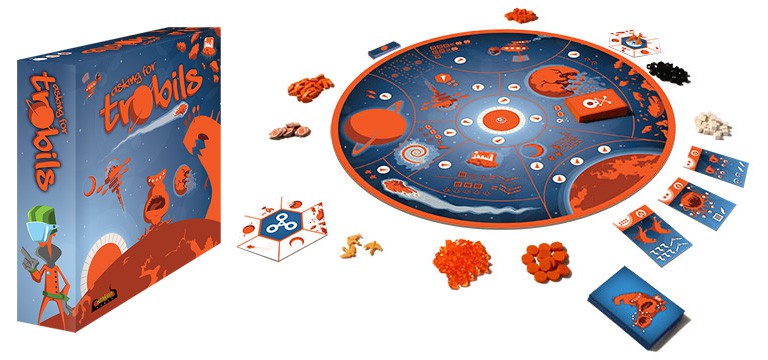

For instance, when teaching Asking for Trobils, people almost always want to look through the RiffRaff cards while I’m talking. The characters are fun, as they were designed to be, but looking through them will have to wait.

STEP 2: INTRODUCE THE THEME

A lot of people skip this because they either think it’s implied, or they feel it’s not necessary to understand the mechanics of the game. The theme of the game can often explain the why.

Them: “Why am I drawing cards when I go to that spot?”

You: “Because you’re a pirate pillaging and the cards are what you get.”

Them: “Oh, I’m a pirate?”

You’ll avoid interruptions like that if you simply explain the theme right away. Use one, maybe two sentences at the most. You’re not trying to dive them into the world of the game right now, let the game do that.

The last time I taught Lords of Waterdeep to someone, my brother kept interrupting by telling them why the purple cubes were wizards, the black were rogues, etc. and how the colors were associated with those representations. I had to take control of the table and tell him to stop. It wasn’t important for them to learn why purple was the best choice to represent a wizard right now, and he was letting his enthusiasm for the theme get in the way of teaching something properly.

With Asking for Trobils, when I introduce the theme, I simply say something like, “Trobils are space vermin that have infected the planet Paradise. We all play Trobil Hunters trying to be the Greatest Trobil Hunter in the galaxy.”

STEP 3: START WITH THE END

Imagine if someone started giving you directions to drive somewhere without you knowing what the destination was. You wouldn’t know why you were making that turn, or even how long these directions were going to be. A journey is so much easier to explain if you give the destination first.

Sometimes this is easy. A lot of games are point accumulation and so saying something like, “The winner is the one with the most points at the end” is a simple way of telling the player how to win. Keep in mind though, the next question in their mind is, “How does the game end?”.

I’ve seen explanations fall apart at this point. When talking about how the game ends, you suddenly find yourself discussing concepts that you haven’t gotten to yet. Sometimes the best thing to do is a quick mention and a “we’ll get to that in a minute”.

Other games can be a little more complicated to explain when it comes to winning. Just remember to keep it simple. Don’t explain how to get to the win yet, just what is required. Use only one sentence.

“In Talisman you win my reaching the center of the board and killing everyone else off.”

“In Dungeon Lords you win by having the most points at the end”

“In Arkham Horror, you win by either killing the creature that rises at the end, or by stopping them from rising by closing gates.”

Since I just said when describing the theme of Asking for Trobils that players are Trobil Hunters, my explaination of how to win flows very easily after that. “You win by having the most points at the end of the game, and you get points by capturing Trobil cards. The game ends when all the Trobil cards are gone. I’ll discuss how to get Trobil cards in a moment.

STEP 4: ON THEIR TURN

People learn best when things are presented to them in their perspective. Tell them what they’ll be doing on their turn. Most games have player mats or cards you can even hand out at this point so that they can follow along.

This usually makes it easy to tie in things that you’ve held on to, such as how to get points, get to the middle of the board, close gates, etc. In some cases, turns are a little harder to explain. In Evil Intent for example, players take their turns almost simultaneously. In that instance you describe what everyone is doing.

When you get to a certain component, such as, “At the start of your turn, draw a card from this deck”, this is when you describe what that deck is and what to do with the cards. There shouldn’t be any more holding back on information. Always try to stick close to what they do on their turn though. If you start talking about how cards work, make sure to explain it from their perspective.

Always approach things from their perspective. What are they doing? Why are they doing it?

“On your turn you either place a ship on the board, or you pick up all of your ships. Placing a ship on the board lets you interact with that location.”

HOW PEOPLE LEARN

The most important thing to keep in mind when teaching is how different people learn. There are generally three different ways people learn; visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. Most people are a blend of all three, although I can tell you that I’m almost 0% auditory. If you talk to me without moving a muscle, it goes in one ear and out the other.

Visual Learners learn best when presented with images, props, and motions. So for instance, if I tell a visual learner that they can move their piece down the point track, they’ll pick up on that lesson better if I pick up the piece while saying this and actually move it down the track.

Auditory learners learn by listening to you speak. This is one of the reasons why controlling the table is important. There should be only one source of information coming their way. Auditory learners also do well if they repeat a summary of what you just said back at you. If you notice a player doing this, then they’re listening to your words more than anything else in your presentation.

Kinesthetic Learners learn by doing. If you feel you might be losing someone, hand them the dice to roll and explain what their result means. Give them the card to hold and look at while you explain it. Get their hands involved. The last time I explained Cosmic Encounters I directed people to actually pick up their ships and place them where I was telling them to place them in different situations.

If you put all of these methods into practice, then you’ll hold everyone’s attention.

THE WRAP UP

Let me just put this out there, you’re probably going to forget something. Especially in a complicated game. I dare anyone to teach Arkham Horror without starting a sentence with “Oh yeah, I forgot to mention…”.

The best way to find out if you’ve missed something is asking for questions at the end.

In some cases, playing a dummy round would be a good idea. You start first and show everyone what to do and why you’re doing it. In a dummy round, nothing is kept secret.

Remember to look people in the eyes and engage them. I like to stand up when teaching at larger tables so that I can reach over to others. Just like the game, try and keep the teaching fun and enjoy yourself.

If you’re interested in Asking for Trobils, check out our Kickstarter page!