There are a few ways to go about getting your game to print. One is to make it yourself. This involves high financial risk, probable disappointment, and a huge investment in your time to advertise, promote, manufacture, package and distribute your game.

Another way to go is to have someone else do all the work, take all the risk, pay you royalties, and free up your time for the next design, playing game prototypes while drinking beer with your friends. Ah, the life!

This is about the second path. The first path is great if you want to start a business and be a successful entrepreneur, because a successful game can make you a lot of money. But you’re more likely to crash and burn with a $20K debt load. Much of the financial risk has been reduced to near-zero thanks to Kickstarter since you can presell your game, but it’s still an awful lot of work manufacturing and promoting it. It all boils down to where you want to go with your company and the risks you want to take.

Back to the article; let’s say you’ve decided to try to place the game with some publisher-manufacturer. How do you proceed?

I’m most familiar with two techniques; emailing and demoing at cons. There are a lot of do’s and don’ts to each of these, but I’ll get to that in a minute.

BE PREPARED FOR REJECTION!

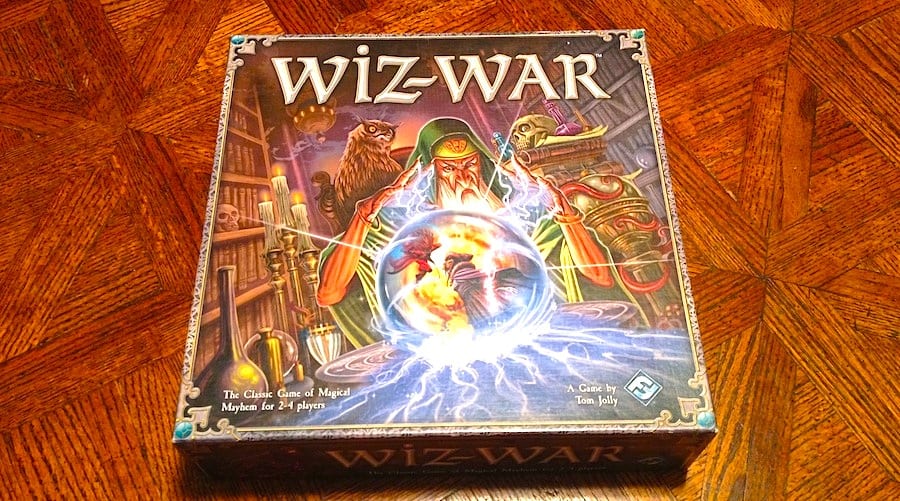

First and foremost, be prepared for rejection. Wiz-War, now one of my most profitable games (now in its 8th edition) was rejected five times way back in 1985. It happens. You better have a thick skin, and pay attention to comments made by the rejecters. They usually know their business. I think I changed Wiz-War every time I got it back from a company. It’s a better game for that.

CONTACT THROUGH EMAIL

It’s hard to pitch a game to a company via email, especially if you have no name in the industry. There’s a standard list of things NOT to do. I’ll mention a few of them here;

DON’T TELL THEM HOW GREAT YOUR GAME IS

They’ll decide this when they play it.

DON’T STATE HOW ALL YOUR RELATIVES LOVE YOUR GAME

This is irrelevant. Relatives and friends are notoriously bad about giving you honest feedback (unless you have a bunch of cutthroat game designer friends like I do – it helps to have a designer circle). It also makes you look like a newbie.

DON’T BE SECRETIVE ABOUT THE GAME FOR FEAR OF “THEFT”

Lack of details about your game will send red flags up for them; it indicates you’re going to be hard to deal with. And it doesn’t exactly excite their interest. “I’ve got this cool game, you want to look at it? I’m sure it will be a best seller.” Into the round file with your letter!

DON’T BRING UP MONEY

If/when they’re interested (after they play your prototype), they’ll usually offer you an advance and royalty (or try to buy it outright).

DON’T INSIST ON AN NDA

(NDA = non-disclosure agreement) Some folks will argue with me on this point, but once again, if you’re trying to convince a manufacturer to look at your game, you want to make it easy for them. If you’re already well-known in the industry, you can probably get away with asking for an NDA. Put yourself in the manufacturer’s shoes, reading your email demanding an NDA. Do I really want to deal with this guy?

DON’T SEND YOUR RULES

And don’t send a PDF of your game unless they ask for it.

And on the flip side…

DO EXPLAIN THE GAME

Enough that they can make an informed decision. Try to do this in less than a page. Tell them enough of the rules that they can get a good mental image of game play. If there’s something unique about the game that’s going to sell it, mention that.

DO ACT PROFESSIONAL

Have someone proof your email or letter. Obey the rules of punctuation and grammar. Why do this? So the company doesn’t think they’re dealing with a moron. Include one or two pics if relevant.

ENCLOSE AN ENVELOPE

If you send a letter, DO enclose a self-addressed-stamped-envelope for a reply. I imagine nobody bothers sending letters anymore, in which case this is irrelevant.

INCLUDE A RETURN BOX

If you end up sending the game to a company, include a self-addressed return box. I dealt with at least two game/puzzle companies that wouldn’t return my prototype because I didn’t include a stamped return box.

Remember that when a game company makes the decision to look at your game, they’re going to read the rules and playtest it at least once. It’s going to cost them a few hundred dollars in labor costs, if not more, just to look at your game. So it’s not a decision they make lightly when they read your email and decide whether to look at your project. They also incur the risk of you being some nutcase that’s going to sue them because you submitted a game about Dragons the same year that they happened to put out a game with a similar theme (this is where acting professional helps a lot). So expect rejection; game companies get a lot of submissions in a year, and unless yours really stands out somehow, it won’t make the grade.

All that said, it wasn’t my preferred method when I started out. Once you’re already on a talking basis with the company, and they know you in the industry, you can email all your pitches with a high degree of trust between parties. But my preferred method was to haul a bunch of well-tested prototypes into a convention and find a company who wanted to look more closely at them.

DIRECT CONTACT AT CONVENTIONS

GET YOUR TIMING RIGHT

Don’t approach a manufacturer’s booth with your prototype when they’re busy. That will just irritate them. When they aren’t busy, ask if there’s someone you can talk to about pitching your game, preferably during some 5-15 minute period after their booth closes up for the night. Make an appointment. They might ask what the game is about before committing to this; be prepared to give a 1 minute explanation that’s interesting, otherwise they might not give you that appointment.

BE PREPARED TO DEMO

At your appointment, be prepared for a detailed 5-minute explanation of the gameplay. They might decide they want to play it on the spot; be ready for that. Likely they won’t play it all the way through (depends), but they might like it enough to say, “Yeah, send that to us. We’ll look at it in more detail and if we like it, we’ll send you a contract.” Here’s a sample of a basic contract. I’ve had contracts over ten pages long, however.

DISCUSS TERMS

This isn’t a bad time to ask about what terms they generally offer. Advance plus royalties? I actually had the misfortune with one company to find out after they accepted my game that they didn’t pay an advance (which is subtracted from eventual royalties, usually); this, unfortunately, often leads to situations where the company can sit on your game for years, then decide they don’t want to make the game after all. You get nothing, and they hold up your design for years.

DISCUSS INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, IF YOU MUST

If you insist on having an NDA, you could mention it in your meeting. They might say they don’t do that. It’s your choice if you want to back out at that time or not. Keep in mind that they can choose to do the same. I remember years back dealing with TSR and signing something from them that said, basically, “if we happen to publish something that looks like your game after reviewing your game, you can’t sue us.” I don’t remember what the legal document was called, but I can understand it; they are constantly designing dozens of games with all sorts of themes and mechanics, and the odds that there’s going to be some overlap between your game and some design of theirs is going to be very high. See my prior article, “Those Bastards Stole My Game!” for more about this.

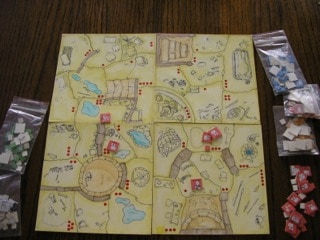

MAKE SURE YOUR PROTOTYPE LOOKS GOOD

Spend a week or two on your graphics; it doesn’t have to be professional, but I assume you have access to a color printer, free graphics software, and full-sheet labels and cardstock; make the tokens and board and cards pretty. Decent graphics add a lot to how the manufacturer views the game. It’s not mandatory, but it improves your odds quite a bit.

Over the years, I’ve pitched games face-to-face to an awful lot of game companies at conventions, and these encounters resulted in most of my sales. I’ve seen Bruno Faidutti hauling around a handcart full of prototypes at Essen doing the same thing. It works. It’s a good way to deal with companies and get fast feedback on whether your game is publishable or not. Also, you get exposed to what’s selling well in the industry. It can’t hurt to know your competition.

Stay tuned for my next entry on what to watch for in contracts. It’s a tricky subject!