Guest Post by Marco Valtriani

Marco Valtriani is an Italian game designer and lead developer for Red Glove publishing. He also runs an Italian version of the Board Game Designer’s Forum: Board Game Designers Italia. Some of Marco’s credits include Godz, co-designed with Diego Cerreti, Vudu, co-designed with Francesco Giovo, 011, and The Super Fantasy Series“

Marco has written extensively in Italian on design theory and practice. We’re delighted that he wrote the piece below in English for the League of Gamemakers.

“OK, WHAT DO I WANT PLAYERS TO FEEL?”

“WHAT DO I WANT THEM TO DO?”

EXPERIENCE

The term “experience” is a pivotal point in many books about game design. It’s one of the main concepts in Schell’s Book of Lenses, and you will find it also in Rules of Play, by Salen and Zimmerman. (see also Mark Major’s piece: Experience vs. Mechanics on the League of Gamemakers.)

We all agree that the game designer designs a game, but, if we think about it, the game itself it is just an artifact. It is an artifact made to convey an experience, which is a combination of actions, thoughts and feelings. So, when we design a game, our focus, our goal, should not be the game in and of itself.

“WE DON’T WANT TO SIMPLY CRAFT AN OBJECT. WE WANT PLAYERS TO LIVE AN IDEA. OUR IDEA.”

So, as designers we create an artifact, but we build it knowing that it is the way we’ve chosen to convey to our audience the desired experience.

TARGET AUDIENCE

If we want to achieve this ambitious goal, the center of our thoughts should not be the mechanics, nor the theme, nor the pieces of the game. The first thing we should keep in mind are the players. Player-centric game design always starts with the question:

“WHO ARE WE MAKING THIS GAME FOR?”

Are we designing for heavy players who like games to last several hours? Are they mathematic thinkers who enjoy calculation? Are they players who are clever with spatial puzzles or abstract problem-solving? Are they science-fiction buffs who enjoy being immersed in a futuristic world rich with technology and alien life forms? Are they families with young kids looking for something easy to teach and play?

Choosing the desired experience, and accordingly, choosing which type of players we want to make the game for, helps us make many decisions about the project, including elements such as genre, theme, complexity, and by consequence which kind of publisher might be interested in our work.

We can also take this one step further and think about a possible list of publishers while starting to wonder about the desired experience: knowing what we want may help us a lot if our wish to see our project published.

DOING THE WORK

When we have a clear idea about what kind of experience we want our players to enjoy, it’s time to grab our tools and work on our game. Our tools are, mainly, two: mechanics, which are the means that allow players’ choices to have a meaning in our game, and theme, that should help the players to “feel” the imaginary space of our game.

As you know, it’s really important to figure out as soon as possible the sources of positive tension and uncertainty in our game, along with the type, frequency, and intensity of interaction between players. All these “gears” should work together to promote the desired experience, being functional to what we want. This will help us streamline the rules, and fine-tune the theme and mechanics by removing every redundant detail.

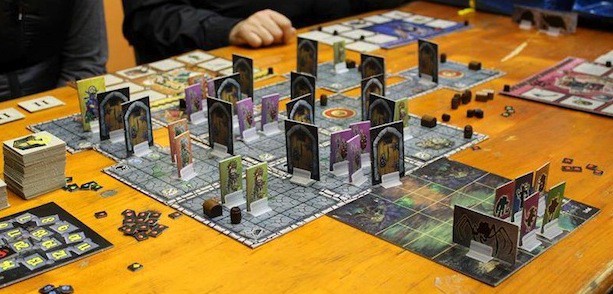

THE SUPER-FANTASY SERIES: DESIGNED FOR THE EXPERIENCE

Everybody has his own method, of course. For me, player-centered design works really well. It allows me to think about a game not just as a system of mechanical gears, and this helps me a lot when I’m searching for the best solution to transmit the idea I have in mind to my players, and it facilitates my attempts to think outside the box.

I use the player-centric method for all my games. When designing the Super Fantasy series, the focus was to re-create the feeling of a hack and slash videogame. So, throughout the design process, I tried to think as a hack and slash player (which was not so hard, as I’m a huge fan of games like Diablo, Torchlight and Bastion).

The gameplay includes meaningful choices about the actions: I could not recreate a gameplay based on reflexes and finger dexterity, so I used a “risk management” system that allows the player to invest “action dice” to do things (move, attack, defend, open doors, smash barrels and so on.) You have a limited amount of dice. Every die spent on an action increases the chance of success, but you have only six dice in a turn, so if you use too many dice on a single action, you’ll be able to perform just one or two things instead of, maybe, four or five.

Also, the secondary mechanics that rule leveling up and special skills are directly controlled by the core mechanism, speeding up the flow of the game and giving a videogame-like feel to everything. The design of monsters and level follows the same principles. In the second chapter of the series, The Night of the Badly Dead, I also added some features suggested by our fans: monsters now can drop items, and they may have random abilities, just as the special monsters in the Diablo series.

You can read more about Marco Valtriani’s player centered-design on his designer diary on BGG: https://boardgamegeek.com/blogpost/23600/designer-diary-super-fantasy-or-hacking-slashing-o

What experiences do you have about player-centered design? What kinds of experiences are you trying to create in your designs?