In Part 1 of this series, I discussed the origins of analysis paralysis and five principles to keep in mind while designing. In this installment, I give you ten methods to reduce analysis paralysis and decision time in your games.

10 METHODS TO REDUCE ANALYSIS PARALYSIS IN YOUR GAME DESIGNS

- 1) Break Down Turns into Steps or Phases

- 2) Impose Limits

- 3) Reduce Turn Length

- 4) Use Hidden Information or Randomness

- 5) Reduce Opportunity Cost

- 6) Escalate Gradually

- 7) Prevent Cataclysmic Change

- 8) Eliminate or Reduce Calculation

- 9) Minimize Visual Information

- 10) Use Simultaneous Actions

1) BREAK DOWN TURNS INTO PHASES/STEPS

The terms phase and step are used interchangeably in different games, and some games use both, but think of them as ways of breaking down decisions into pieces, and controlling the timing of events in your games.

TAKE PRESSURE OFF YOUR PLAYERS BY ALLOWING THEM TO PUT ONE FOOT IN FRONT OF THE OTHER BY MAKING BIG DECISIONS IN STAGES.

Individual Player Turn Phases: Break down a player’s turn into a finite number of phases. Each phase allows a different type of action to be taken. Usually, having phases will imply a set order, like in Dominion, with its two phases: Action, then Buy, or in Magic, the Gathering – untap, upkeep, draw, and so on. In some games, it makes sense to allow phases to occur any order: In many games you can move and attack, or attack then move.

In one of my favorite games, The Manhattan Project, each turn you either Place Workers or Retrieve Workers, these can be thought of as alternating phases. This sounds very simple, and it is, but this simple framework allows players to focus their attention on the complexities of the resource economics and the scarcities or abundance of opportunities available.

Game Phases: Another option is to have all players take an action or make a certain type of decision at a given time. Examples: (a) All players draw a new hand of cards (b) All players remove their workers from the board. (c) Each player may build one building.

2) IMPOSE LIMITS

Not all limits make choices easier, but usually removing options makes it simpler to choose from the options that remain. You can remove insignificant choices in order to limit the factors players need to consider. For example, rather than letting a player place a new unit anywhere on the board, require a unit to originate from a designated space. The player no longer has to make the added decision of where to place the unit, and can instead focus on how to use that unit.

If a player has 11 actions to choose from each round, expect rounds to be slow, even if each of the 11 actions is simple (this is one dial you don’t need to turn up to 11). Give them 3. Reducing hand size in most games will reduce options and speed things up, but keep in mind that consumable cards are also a resource, so when hand size gets too small, the value of each card can increase to the point of making any given card harder to part with.

In Carcassonne, each turn a player gets only one tile and places that tile, but they still usually have several placement options and potential strategies to consider. Imagine if players drew 2 tiles instead? 3? What if they drew 5 tiles but could place 2 each turn? On the surface, these changes might sound like “better” or “meatier” versions of the game, with more options and more control. The reality is players would agonize over every possible combination of tiles each turn, slowing the game to a halt, and sucking the fun right out.

DON’T SUCK THE FUN.

3) REDUCE TURN LENGTH

Related to the Carcassonne example above, keeping turn length short allows players to continue where they left off each turn. Long turns breed even longer turns. (See Dominant Species) Waiting players might be able to plan their next move, but that will wear out fast. Players can be waiting so long they forget their strategies, lose track of the flow of the game, or worse still, forget how to play entirely. Nothing is worse than having to re-tell what’s happened over the last three turns every turn. Reducing the number of actions a player takes each turn can help keep things moving right along. In my game, Stones of Fate, players take only two brief actions each turn, which is important in a game that involves memory. Reducing turn length is especially important in games that support a large number of players.

4) USE HIDDEN INFORMATION OR RANDOMNESS

Hidden information is a fascinating way to make decisions easier for players, and not always an intuitive design choice. One might assume that when everything is visible in a game, that it would follow that players would be able to make better decisions more easily – because all the information they need is right in front of them, like in Chess, Checkers, Mancala, and countless abstract games.

But when all the data is right in front of you, even when it is not all that complex, players can have great difficulty synthesizing it all and applying their strategy. Maddeningly long pauses can occur in games where people believe that the perfect decision can be found.

In Lords of Waterdeep, players each have a hidden secret bonus (the Lord card) based on accomplishing goals of a certain type; the equivalent of a “Guild” type card in many games. Because other players don’t get to see the bonus cards of their opponent, they cannot usually mathematically determine the winner prior to the end of the game. And while they may be able to surmise what moves will be beneficial or harmful to their opponents, they cannot automatically know precisely how beneficial or harmful those moves might be. Because of the hidden information, players cannot know the “perfect” move, and have to content themselves by choosing from good available moves.

I plan to delve more deeply into the concept of hidden information in a future blog, as it is the core of my game Replicant.

Randomness, of course removes some certainty about the value of decisions, and is a vastly complex and interesting topic. Rather than delving into randomness here, I will point you to the lecture notes of the master game designer, James Earnest (Cheapass Games). Volatility in Game Design

5) REDUCE OPPORTUNITY COST

Opportunity cost represents what is lost or given up when a given decision has been made: the road not taken. This method is a little trickier than some of the others to implement. We like decisions to matter in games, and consequently, we tend to design them so that players have to make tough choices and accept some sacrifice as they go about pursuing their goals.

DESIGNERS NEED TO BE CAREFUL THAT THEY DON’T CREATE SO MUCH FEAR OF REGRET THAT PLAYERS WILL GET STUCK IN THE QUAGMIRE OF ANALYSIS PARALYSIS.

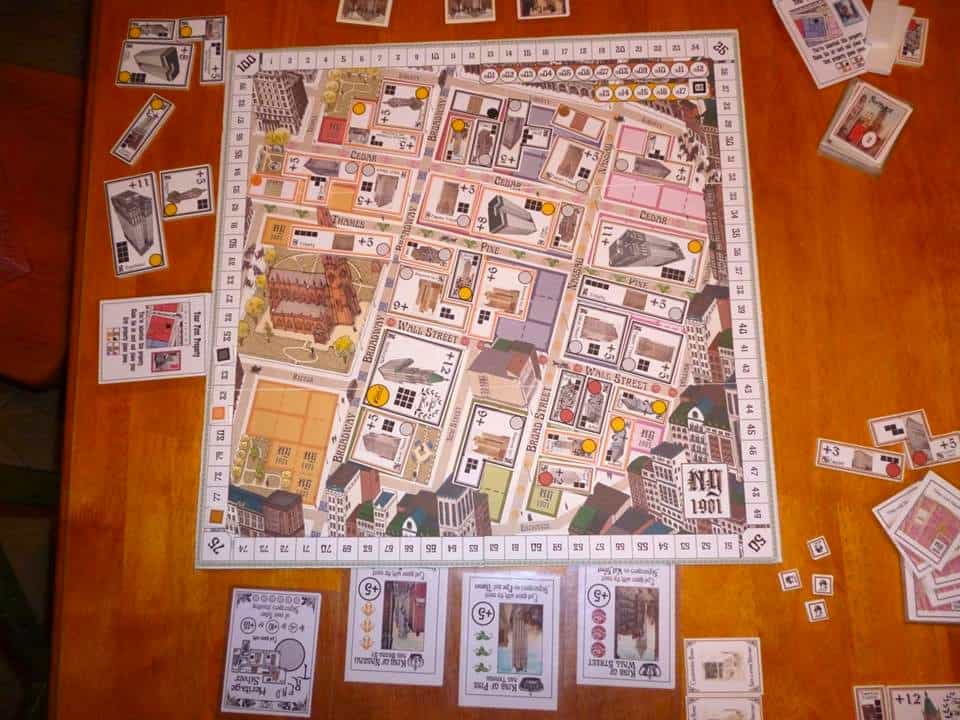

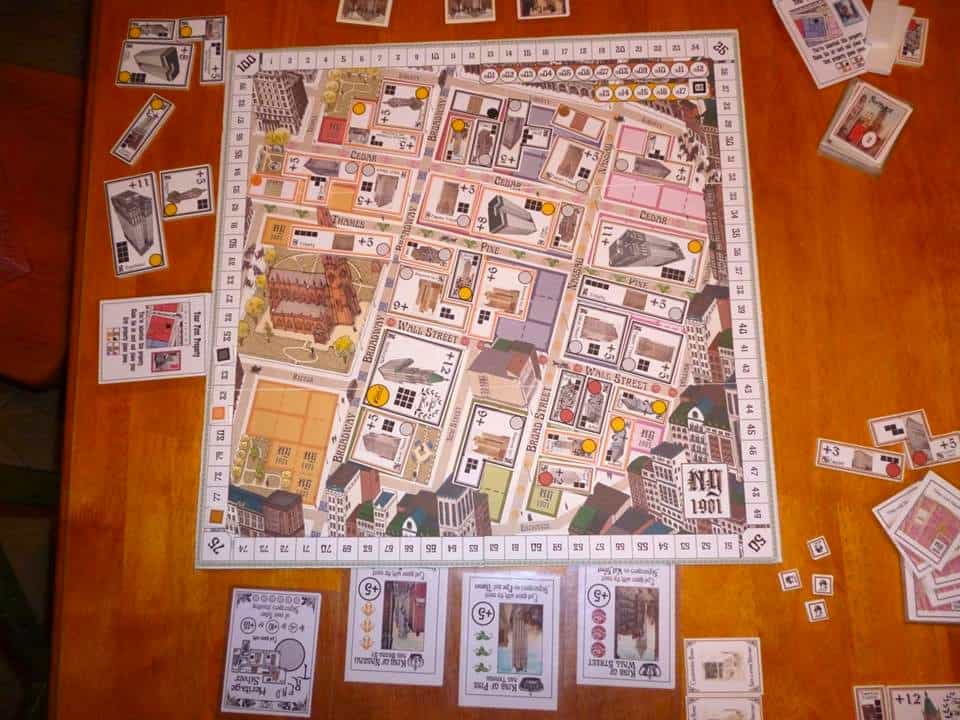

I recently playtested a great new game in development called New York 1901 by Chenier La Salle. In this game, players are building the early skyscrapers that created New York’s iconic skyline. In an early version of the game there were several face-up bonuses that all players were competing for. Players received points for the buildings they built, and additional bonus point based on which streets they were adjacent to. When we approached end of the game, we could mathematically calculate the exact effect of our moves, and discovered that nearly every good move available involved giving up another equally good move. There were so many bonuses, we all knew the bonuses, and the bonuses were valued equally, so the opportunity costs were high. We couldn’t make a move without regret. We struggled through those last few turns and gave our feedback to the designer, who is continuing to develop what is certain to become a great game.

6) ESCALATE GRADUALLY

It’s ok for things to start small. Start your game with just a few pieces, just a few cards, just a few resources. Let the first few choices in the game be simple, and allow the game to slowly ramp up to increased complexity. The pace and simplicity of the early turns will give players a chance to get warmed up, so that when complexity builds, they’ll be able to handle it more readily than they might have straight from the gate. In addition, starting small can reduce the impact of early game decisions, unless, of course, this is one of those worker placement games that allows some players to gain workers while others do not. Then you can be just be demolished by unlucky or poor early game moves (Upon a Fable).

A game that begins with tons of pieces, hour-long setup, and many choices can be daunting to a new player. (Runewars)

7) PREVENT CATACLYSMIC CHANGE

If the game state changes between turns, that is expected and usually a fun part of a game: there are more enemies now, you lost a monster, one of the spots on the board you wanted is gone, a new item is available. We like those dynamic situations. But changes in game state require shifts of strategy, so when everything changes, a player must spend a long time crafting their response and anticipating all of the possible changes that will occur the next time around.

When there is some degree of stability in the game between turns, players can plan their next moves. They don’t have to wait until it’s their turn to have an idea of what they’ll do. Dominion is great this way. You’ve got the market of cards in front of you the whole game, and you can be looking at and thinking about the cards you want next, and plotting how you’ll get them.

8) ELIMINATE OR REDUCE CALCULATION

Tokens, counters, cubes, and tracks can greatly reduce the need for doing any significant math beyond a little addition and subtraction. Often, with the right visual cues, players don’t even need to really do the math, they can just use estimation to determine greater than and less than, and heuristics to arrive at a probable outcome.

Let players who want to calculate do so, but allow players who don’t like math the opportunity to play your game by gut instinct.

If your game requires long division or adding fractions, you’re probably doing something wrong. Unless, of course, your game is a math game, like Tom Jolly’s Got it!

9) MINIMIZE VISUAL INFORMATION

There’s really only so much data and so much visual information that players can assimilate before their heads explode. So, unless the goal of your game is to explode the heads of players, try to reduce the number of pieces, different colors, and quantity of data in your game. (Admittedly, there are some HUGE games out there these days that are well loved. I once saw players huddled around a ten-foot long version of Arkham Horror for a quick, 12-hour game.)

Find ways to make your color schemes complimentary, minimize the components required in order to display a given type of data, and leave enough space for players to tell things apart.

Ultimately, players need to be able to size up the game situation quickly in order to facilitate decision making.

IF THE VISUAL INFORMATION IS TOO CLUTTERED OR CONFUSING, THE PLAYER ISN’T USING THEIR MIND TO PLAN STRATEGY, THEY’RE USING THEIR MIND TO TRY TO INTERPRET THE INCOMPREHENSIBLE MESS OF HIEROGLYPHS YOU CREATED.

10) USE SIMULTANEOUS ACTIONS

While not appropriate for many games, simultaneous actions, like the role selection in Race for the Galaxy, can really speed up a game, and simplify the process of decision making. It can also lead to big surprises and game swings, so it should be used with caution.

So there you have it, are you paralyzed now? Dumbfounded by the overwhelmingly vast options you have as a game designer? Or are you jazzed and ready to jump back into that game that you love to build but it’s still a pain. Good luck, and happy designing!