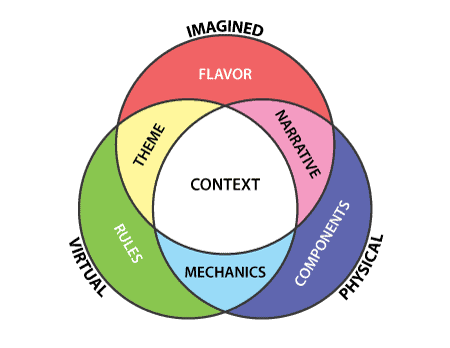

Most conversations about theme and mechanics treat games as if those are the only two elements a game has. Some comments make it seem like there’s this linear scale with “theme” on one end and “mechanics” on the other. Other comments paint a picture of a Venn diagram with two non-overlapping circles.

THE REALITY IS THAT GAMES ARE MUCH MORE COMPLICATED.

“Theme” and “Mechanics” mean a number different things in different situations. So it becomes very fuzzy to have a conversation about which is more important in designing, playing, or purchasing games, because each participant in the conversation might have a different idea about exactly what those terms are encompassing.

For the sake of this article, I’m going to define some different terms in hopes of presenting a more accurate model of a game’s elements.

Flavor: Flavor is thematic detail in a game that has no impact on how the game plays. It exists purely in the Imagined circle, which deals with emotions and feelings you want the player to bring with them. Bits of text giving a glimpse into a city’s history, atmospheric art in the rulebook, or a portrait of a random, nameless side character are all examples of flavor.

Rules: This is the theoretical system or parameters of the game. It exists purely in the Virtual circle, which deals with concepts you’re introducing to the player. “You select one option and pass the rest” is an example of the rules you’ll be imparting to the player.

Components: These are the bits that make up the game, cards, boards, dice, pawns, and so forth. These exist purely in the Physical circle, which is all the real-world parts of a game (including the players).

WHEN YOU START COMBINING THESE, YOU GET MORE COMPLEX LAYERS.

Imagined + Physical = Narrative

Narrative is the unique sequence of events that players experience during any specific game session. In a themeless, abstract game, this narrative is literally the actions that players take, such as “I place my stone at the intersection of the 4th row and the 5th column.” But in a game with a theme, the narrative changes. Rather than “I put my wooden token at the intersection of those three hexes,” it becomes something more like, “I build my settlement by the wheat, sheep, and wood”.

Physical + Virtual = Mechanics

Where the rules set up the game’s conceptual parameters, the mechanics are the game’s engine. Mechanics are an interactive concept: They’re how the players use the rules to come up with strategy.

Virtual + Imagined = Theme

Where flavor has no impact on the game, theme does. Themes set up parameters for how you expect the game to take place, what behaviors you expect to take, and how you’ll be interacting with others. For example, a zombie theme would probably include the expectation of suspense and perhaps cooperative play, but not include the expectation of political intrigue or medieval warfare.

Put them all together and you get…

CONTEXT

As you might guess from the fact that it rests in the intersection of all three circles, context is really important! Context is how players understand the game as a whole and their role in it.

CONTEXT CAN CHANGE BY SCOPE.

Context is a high-level view of what the players are doing and why they are doing it. You can look at it in the moment (What are you doing and why are you doing what you’re doing it: You build cities in this game to increase the reach of your civilization) Are you yourself or are you playing a role?

CONTEXT IS SCALEABLE.

Simple games may not need a strong theme, since they are easy enough to understand. The more complex or seemingly contrary a game’s mechanics are, the more important theme is as an ingredient because of how it modifies and builds the context. This can also allow a personal narrative to take the forefront, such as how well you know your fellow players.

CHANGING THEME CAN CHANGE CONTEXT

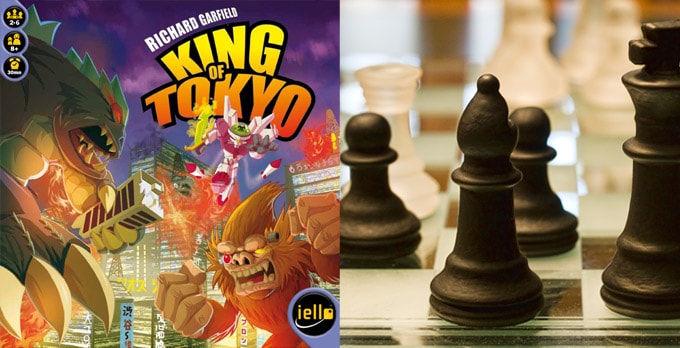

Even an abstract game has context. In a game of Go, a player understands they are trying to best another player by pitting strategic skill against strategic skill. This illustrates another function of theme. A theme can alter the context of a game to make the social interaction less contentious. If you see the game as being Cyber Bunny vs Gigazaur, when one of them stands triumphant in Tokyo it says nothing about Josh or Gary the players. When the theme is abstract, there’s less of a buffer and the game becomes more competitive.

But when a theme is poorly matched to the mechanics and narrative, the context suffers. Take a game like Trajan, which makes no attempt to fit the theme and the mechanics together into a good context. It paints a blurry picture of Roman society, but there is nothing to explain the mancala mechanic, making it an awkward method of choosing actions. Theme makes you question why you don’t have options you think you should for your role and your goals, creating dissonance and an imbalanced context.

CHANGING MECHANICS CAN CHANGE CONTEXT

The components you use and the rules you follow also have a big impact. In Oceanica, I deliberately chose the mechanics of rolling dice to create random results and drafting those resources. The mechanic of randomization creates a scarcity. The current theme, which is that you’re competing for the last remaining resources of a flooding planet, was overlaid on top of this to create a unified context of a chaotic environment.

The flavor and theme could completely be changed – spaceships mining a dangerous field of asteroids, perhaps – and work equally well. But if the theme were changed to something other than that chaotic environment – building a static civilization, for example – the mechanics as they are would not reinforce that, and the context would suffer.

CHANGING NARRATIVE CAN CHANGE CONTEXT

The trickiest thing for a game designer to affect is narrative, because this is the thing that’s most reliant on the players, not the components. If your friends invite over their alpha gamer friend to cooperative game night, that will affect the narrative. If you break for pizza in the middle of a game, that will also affect the narrative.

This is where good marketing and graphic design comes in. Are you making your game attractive to the people who will create the best context for the mechanics and theme to thrive? Are you using flavor graphics that let them know what their role will be? Are you conveying how long the game plays or how complicated it will be with your components? Did your publisher get that key reviewer to talk it up and guide your audience’s expectations? Did the player find it at Toys R Us or in a war game hobby store?

Good marketing will help people come into the game with the narrative most conducive to building the right context, whether that’s “I’m here for a fun game that will have me out of my seat pantomiming the chicken dance with my kids” or “I’m here to match wits with my smartest friend and build a strategically poised galactic empire over the next 8 hours”.

This is not meant to be a definitive, authoritative breakdown of all the aspects of a game. Feel free to disagree with the specifics of how I’ve defined terms, or where I’ve put labels in the diagram. But the takeaway you should be getting from this is that games are complex entities. Reducing them to a flat heads-or-tails picture ends up missing a lot about how the physical parts of the game, the imagined parts of the game, and the way players interact with the game all have an effect on each other.

“WHAT SHOULD A DESIGNER FOCUS ON?”

This is the core question debated by Luke Laurie and Peter Vaughan in their corresponding articles on this topic. This tends to be a polarizing question, but the reality is that it doesn’t really matter. Whether you should start thinking about the imagined parts of a game (such as theme) or other elements first depends largely on what you want your players to experience.

I talked a bit before about designing for the experience. Theme makes sense if you want the play experience to be driven by the imagination (Fantasy or Narrative aesthetics). Mechanics make sense if you want the play experience to be driven by more intellectual activity (Challenge or Discovery aesthetics). You can start with any of the other categories I defined above too. The main thing is, after you find a starting place, you need to quickly reach a point where you can tie everything together with a strong context, and then maintain the integrity of that context as you add and change different parts of your game.